16a. Study selection – Results of the search and selection process

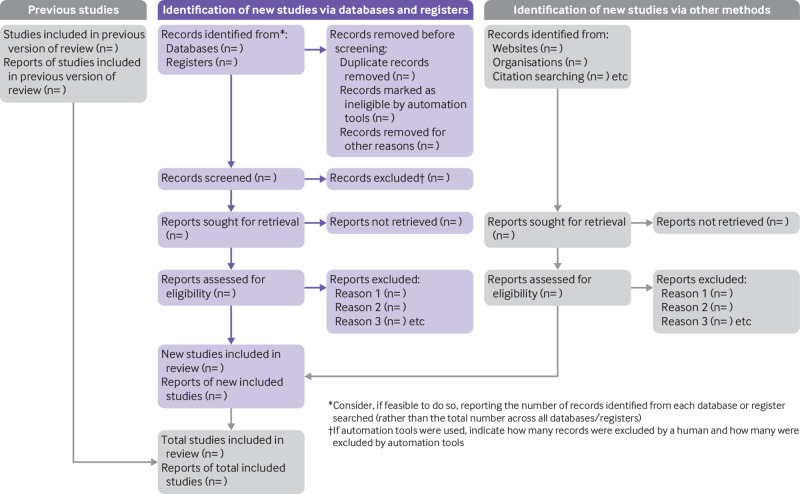

Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram (see Figure 1)

Essential elements

Report, ideally using a flow diagram, the number of: records identified; records excluded before screening (for example, because they were duplicates or deemed ineligible by machine classifiers); records screened; records excluded after screening titles or titles and abstracts; reports retrieved for detailed evaluation; potentially eligible reports that were not retrievable; retrieved reports that did not meet inclusion criteria and the primary reasons for exclusion (such as ineligible study design, ineligible population); and the number of studies and reports included in the review. If applicable, authors should also report the number of ongoing studies and associated reports identified.

If the review is an update of a previous review, report results of the search and selection process for the current review and specify the number of studies included in the previous review. An additional box could be added to the flow diagram indicating the number of studies included in the previous review (see Figure 1).1

If applicable, indicate in the PRISMA flow diagram how many records were excluded by a human and how many by automation tools.

Explanation

Review authors should report, ideally with a flow diagram (see Figure 1), the results of the search and selection process so that readers can understand the flow of retrieved records through to inclusion in the review. Such information is useful for future systematic review teams seeking to estimate resource requirements and for information specialists in evaluating their searches.45 Specifying the number of records yielded per database will make it easier for others to assess whether they have successfully replicated a search. The flow diagram in Figure 1 provides a template of the flow of records through the review separated by source, although other layouts may be preferable depending on the information sources consulted.3

Example

“We found 1,333 records in databases searching. After duplicates removal, we screened 1,092 records, from which we reviewed 34 full-text documents, and finally included six papers [each cited]. Later, we searched documents that cited any of the initially included studies as well as the references of the initially included studies. However, no extra articles that fulfilled inclusion criteria were found in these searches (a flow diagram is available at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233220).”6

Training

The UK EQUATOR Centre runs training on how to write using reporting guidelines.

Discuss this item

Visit this items’ discussion page to ask questions and give feedback.